“…the very processes of learning constitute the political mechanisms through which identities are shaped, desires mobilized, and experiences take on form and meaning.”

— Henry A. Giroux.

While volunteering at the opening of the Williams Street bikeway in Ann Arbor, I met an eight year old girl. She proudly rode her bike alongside her family, excited to be trying out Ann Arbor’s first ever protected two-way bike lane. It was a cold day but avid bicyclists came out to see this further step towards embracing bike culture in the city.

I had brought some signs to give out to anyone interested in my public pedagogy project. As I was explaining one of the signs to a couple of UM students, the eight year old girl walked her biked over to us. She was immediately intrigued and asked, “What does ‘3 FEET’ mean?” I explained and demonstrated that in the state of Michigan drivers are required by law to give at least three feet between their car and a bicyclist rider, when passing. Upon hearing this, her face lit up. She immediately wanted a sign because she never liked when cars drove by her while she was riding her bike. Her mother further explained that they primarily ride together in quiet areas of the city, where cars pass through more rarely. This was because her daughter felt scared when cars passed.

Here we were at a literal ground breaking event: a protected bikeway covering 1/3 of a mile in downtown Ann Arbor. Yet, 1/3 of a mile isn’t really that great of a distance. It seemed that this young girl needed more to feel safe while bicycle riding and maybe this sign could help with, in the words of Giroux, mobilizing that desire.

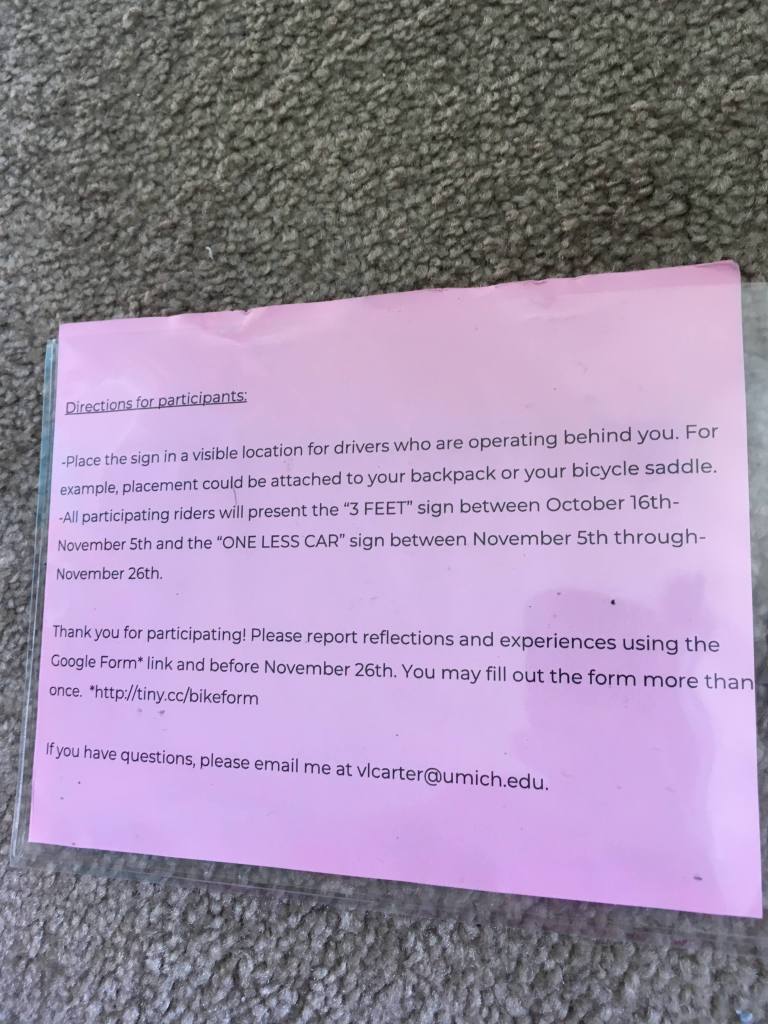

I began this public pedagogy project with aspirations to “empower bicyclists and enlighten drivers” on the University of Michigan campus. I had plans to create three different signs and distribute them among 50 UM students. I designed the signs digitally, printed them out, cut them down and fitted each with a piece of strong cardboard into a plastic paper protector. Two fasteners were clipped to each sign so that bicyclists could attach them to their bike with ease. Because this process was rather labor intensive, I settled on distributing only two signs to 25 people.

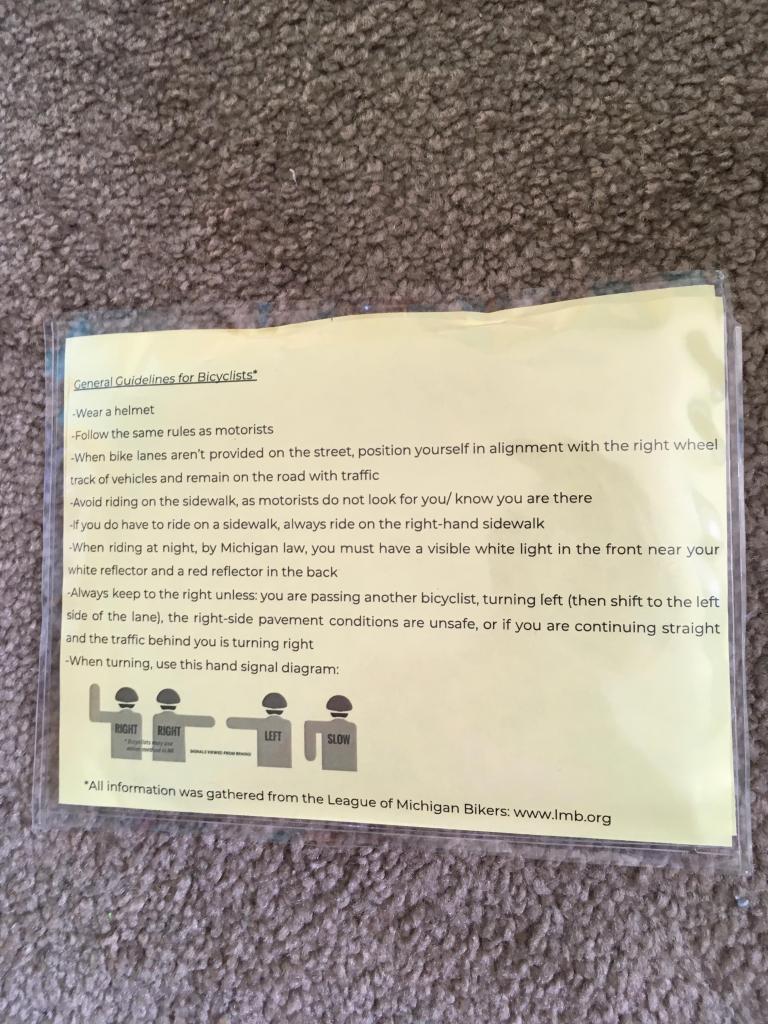

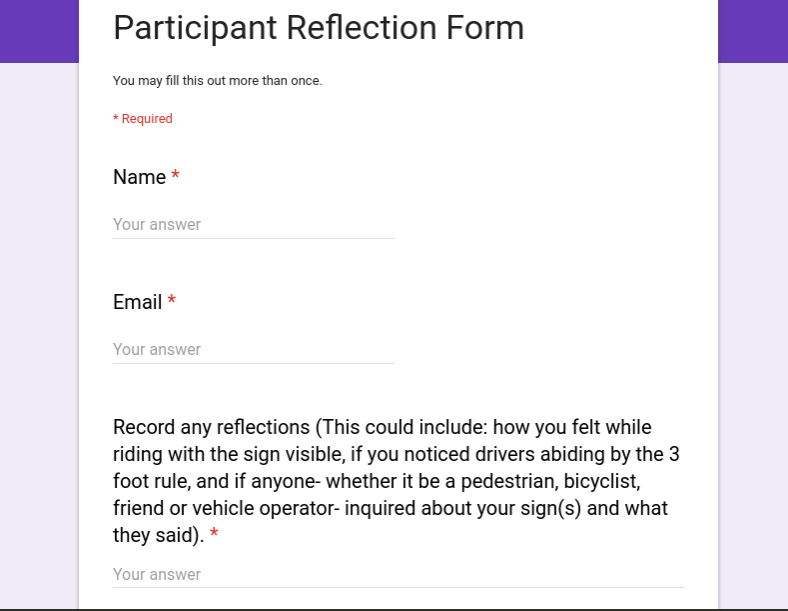

On the back of the ‘3 FEET’ sign were a list of Guidelines for bicycle riders to follow. I formed the list using the What Every Michigan Bicyclist Must Know booklet created by the League of Michigan Bicyclists (LMB). The ‘ONE LESS CAR’ sign explained the project process in further detail and provided participants a link to a Google form where they were to record reflections regarding the project.

Initially, I was able to quickly find about ten friends and/or friends of friends to participate. The remaining fifteen participants were rather difficult to recruit. The first guideline listed on the back of the ‘3 FEET’ sign was “Wear a helmet.” This may have deterred those who don’t wear one from participating. One student I approached at the School of Education bike rack did not want to participate after reading this guideline and because “she didn’t bike much.” She did inquire about the meaning of ‘3 FEET.’ While I was unable to recruit this student to participate, at least the project still supplied learning opportunities and discussion for her. Another participant recounted that several people stopped him and asked what ‘3 FEET’ meant. One of my friends expressed a greater inclination to “bike more responsibly” while riding with the signs. A peer of mine also shared that she has been more mindful of bicyclists while driving, since hearing about the project.

My intent of this project wasn’t to judge fellow bicyclists and their riding habits but, rather, unite us to follow basic guidelines that promote safety. By following the same guidelines, bicyclists would better assert their right to share the road with vehicles in a more organized fashion. With some bicyclists using the sidewalk or a combination of the sidewalk and the road, it is more challenging for us as a group to convince drivers to be mindful of our presence. I planned to achieve this uniting of bicyclists by distributing the two signs and asking all participants to display their signs during the same time frame so that, ideally, all across town we could be seen.

Though, instead of uniting, the guidelines sometimes deterred people from participating, as seen with the student who neglected to participate after discovering the guideline to wear a helmet. This made me realize that public pedagogy should support a group’s needs and desires through discussion and joint efforts. This is more effective than directly instructing a group to take action without hearing their thoughts and ideas on the matter.

In the words of Henry A. Giroux (2016), “Pedagogy in this sense is not reduced to the mastering of skills or techniques. Rather, it is defined as a cultural practice that must be accountable ethically and politically for the stories it produces, the claims it makes on social memories, and the images of the future it deems legitimate” (p. 4). Similarly, I developed this public pedagogy project as a means to teach bicyclists to “master” a set of guidelines while biking on the street and to teach drives to “master” the ‘3 FEET’ rule. In reflection, I should have created a weekly space for participants and interested drivers to share their ideas on biking and driving culture. This way, the claims made on “social memories” are shaped by all stakeholders, rather than just my initial thoughts and actions on the matter. Furthermore, we as a collective group, of both bicyclists and drivers, would discuss implications for a “legitimate future,” rather than solely my voice and/or the voices of bicyclists deciding upon that future.

As aforementioned, I also initially intended for the participants to primarily be students on campus. This was because a lot of unsafe biking occurs among campus bicyclists. Each class I made an announcement about the project, but none of my peers rode bicycles or showed interest in participating. Then, Angie Calabrese-Barton shared that her husband commutes to work on a bicycle and Matt Ronfeldt, a professor of mine, also offered to participate. At this point, I realized that the project could benefit from a diverse group of participants in order to better represent the demographic of bicyclists in the area. Again, I had a particular goal in mind without considering the biking community as a whole.

It also became apparent that not only were participants’ backgrounds diverse but their viewpoints towards the project and towards biking culture in Ann Arbor varied tremendously. When one participating professor agreed to take the two signs, he commented, jokingly, that drivers will see the ‘3 FEET’ sign and react negatively. He said that rather than providing the proper distance when passing, drivers may purposely drive closer to his bike in order to demonstrate their animosity towards the sign’s reminder. Other participants expressed similar sentiments, stating the sign was almost like a target on their back. In fact, on the Google reflection form a bicyclist expressed that, while riding with the ‘3 FEET’ sign, “a driver purposefully passed within inches. When they were stopped at a light, I knocked on their window to tell them what they did was illegal, but they already had the “I’m guilty” face on and refused to talk to me.”

In contrast, a doctoral student from Lima, Peru was rather surprised by my initiative for the public pedagogy project. He explained that he felt extremely safe biking in Ann Arbor in comparison to Lima. In Lima, cars are the sole means of transportation and bike lanes are nonexistent. He even stated that any attempt to ride a bike comes with a very high risk of being injured or killed. He did confirm that Ann Arbor drivers have yelled at him while he was riding his bike but this kind of confrontation doesn’t bother him.

I began to wonder if the signs were effective in serving their pedagogical purpose. That is when I met the eight year old girl on the protected bikeway and observed her eagerness to participate in the project. As previously stated, the intention of the project was based solely upon my perspective and I placed that perspective upon others/participants. Some agreed with my ideas about bike culture in Ann Arbor and, as evidenced above, others did not. One couple I approached at the opening of the bikeway asked how the project was disrupting dominant cultures when it was very clear, through the event we were present at, that Ann Arbor already has a very friendly bike culture.

The previously mentioned Giroux quote emphasizes the importance of public pedagogy going beyond a transmission of codes or information. It must also be culturally and historically aware of the messages it is sending. Sandlin, O’Malley, and Burdick (2011) state that the “lingering tension in public pedagogy scholarship… centers on developing a distinction between public pedagogy and schooling” (p. 363). I taught public school for two years and trained through a teacher preparation program. Both of these spaces unknowingly advocated for learning to occur through “schooling” and I was also complicit in producing this schooling. During this first semester in graduate school, I quickly learned the detrimental affects of “schooling.” More often than not, “schooling” occurs within an institution that promotes dominant narratives such as white supremacy and authoritarian methods with a lack of self-awareness.

Often institutions that promote authoritarian methods expect learning to be a passing of information from the teacher to the students and any opposition to the teachers’ ideas are not welcome. According to Sandlin et al. (2011), scholarship too often views public pedagogy through an institutional lens. I may be doing this as well within the lens of this project but I still think the project had positive outcomes. I was able to hear and critically witness participants’ perspectives. Unlike “schooling,” the learning involved in this project physically occurred outside, where there’s space for opposition and differing perspectives. I think one of the greatest benefits of public pedagogy is that it fosters critical awareness of itself and there is opportunity for participants to critique and question the project itself. This allows for participants to take what they find beneficial from the project. While such an act demonstrates individual agency within public pedagogy, there is the possibility of collective unity to be present.

One of the participants was a graduate instructor and offered to take a few signs to his class, knowing that a few of his students rode bicycles to class. In the Google form he expressed that “The project thus empowered me and my student to feel like we have some kind of a bond that continues outside of the classroom: we belong to a community–a self-conscious community–of bikers.” Even though some participants expressed opposing perspectives towards the status of Ann Arbor’s bike culture, there was still the opportunity for collective bonds to form.

Unfortunately, it snowed two weeks before the end of the project. I stopped biking and several other participants did too. Ann Arbor struggles to clear the roads for cars, let alone the bike paths for bicyclists. With the combination of slippery and icy pavements and an even narrower road, I personally felt even more unsafe biking in winter conditions.

Soon my husband and I resorted to driving our car again. We observed brave bicyclists navigating the difficult conditions all across town. As aforementioned, nearly every road still wasn’t plowed even two days after the snowfall. Then we saw something quite surprising. Before even plowing Williams Street for vehicles, the city had cleared the protected bikeway. This 1/3 mile stretch of pavement was the only space void of snow.

The question kept reappearing: is this public pedagogy project unnecessarily telling a bike friendly city to be more bike friendly? In comparison to other cities across the country or the world (Lima, Peru), Ann Arbor does well to promote biking culture. I would argue that the city is doing most of this positive promoting and there still exists resentment among drivers around the city. I rode my bike with the ‘3 FEET’ sign on for one mile down East Stadium Boulevard a few weeks ago. For a short part of it, there is no bike lane at all. The average speed limit is 35 miles per hour, which felt alarmingly fast when cars passed by. People were walking and running on the sidewalk so I didn’t feel I could utilize it as an alternative to the road. Furthermore, the road has a total of four lanes, with two lines dedicated to both directions. This meant that cars could use the lane farthest from my bicycle when passing but, even with minimal traffic, vehicles were still passing very close to me.

In the above example, the ‘3 FEET’ sign didn’t quite have its intended affect on drivers. During the time I participated in the project, I primarily rode on South State Street from my apartment to campus. Generally, I found drivers gave three feet, if not more, when passing me while I had the ‘3 FEET’ sign present. This is visible in the video below where my husband and I bike South State Street together, with our signs presented.

One can also see in the video that, in some parts, the bike path needs heavy reconstruction and, in other parts, the pavement is still intact. Furthermore, while we were riding, we passed a group of runners on the sidewalk (see screenshot below). Many drivers express that bicyclists should simply use the sidewalk but here evidences why that isn’t always possible. In addition, sidewalks can be uneven in comparison to the road.

The successes of this project shows that bicycles are vehicles. They are vehicles in sense that they deserve space on the road and they are vehicles in a sense that they bring forth the possibility of a better future. As evidenced in the above photo, the signs lead drivers to provide more space to bicyclists. During this project it was also evident that a dominant car culture still exists and the ‘ONE LESS CAR’ sign attempts to disrupt that culture. The sign also reminds us that, as Ann Arbor’s downtown population increases, bicycle riding will serve as one way to combat urban congestion and traffic. Moreover, as our planet continues to heat and climates continue to change increasingly and quickly, the desire to utilize bicycle riding as a mode of transportation has also increased. It is a way for an individual to personally combat the impact of climate change

Though this project didn’t touch upon the work of Taylor and Hall (2013), it is important to highlight how their study further shows the power of bicycles in bringing forth a better and just future. Taylor and Hall provided both bicycles and the space to learn about bicycles for African American youth living in an urban area. Many resources in the youth’s neighborhood were not within walking distance and to have access to a bicycle enabled a new possibility for mobility. At the end of the study, the youth benefited from more than just access to self-provided transportation, they also “developed technically-articulate criticisms of the built environment in their neighborhoods, and imagined new forms of mobility and activity for the future” (p. 65).

In terms of policy, Ann Arbor Downtown Development Authority has plans to install another protected bikeway on First Street in 2020. The bikeways are positive steps towards embracing bicycle culture in Ann Arbor but, outside of them, roads are still uneven and drivers continue to dominate the road. One way I plan to continue to strive for further social change within Ann Arbor’s bike culture is through working with local biking groups. I met many people at the opening of the bikeway. I also met a board member and volunteer of Common Cycle, a group that empowers bicyclists to be knowledgeable of bike maintenance through training, and the co-lead of the Bicycle Alliance of Washtenaw.

These groups work together to empower bicyclists and promote their rights, so that youth, like the eight year old girl I met, can feel safe while biking and be eager to continue bicycle riding throughout their lives.

References

Giroux, Henry A. (2016). Cultural Studies and Public Pedagogy. Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory, DOI 10.1007/978-981-287-532-7_301-1.

Sandlin, Jennifer A., O’Malley Michael P., & Burdick, Jake. (2011). Mapping the Complexity of Public Pedagogy Scholarship: 1894-2010. Review of Educational Research, 81(3), 338-375, DOI: 10.3102/0034654311413395.

Taylor, Katie Headrick & Hall, Rogers. (2013). Counter-Mapping the Neighborhood on Bicycles: Mobilizing Youth to Reimagine the City. Tech Know Learn, 18, 65-93, DOI 10.1007/s10758-013-9201-5.